Author: Mark Winfield, Professor, Environmental and Urban Change, York University, Canada

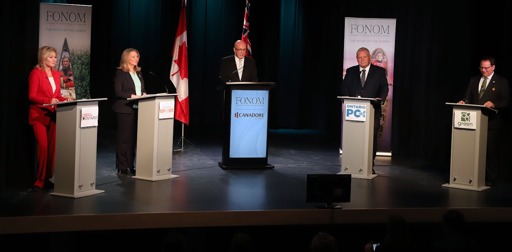

Ontario Premier Doug Ford has justified his early election call on the need to respond to United States President Donald Trump’s threat to impose 25 per cent tariffs on Canadian imports.

While the threat of tariffs on all Canadian imports has been paused — although Trump has since slapped levies on all steel and aluminum imports into the U.S. — Ontario voters need to reflect more than ever on the province’s circumstances and the performance of its government as they prepare to head to the polls next week.

The Ford government’s approach to the environment and climate change, as well as its policies on a range of other issues like housing, health care and education, is best understood in the context of its overall “market populist” approach to governance.

Several defining features of this model have emerged over the past six and a half years under Ford’s rule.

Well, let’s look at a case. The Ontario Teachers Union is a major political force. But somehow, it doesn’t go to improving affairs for Ontario teachers and certainly not for Ontario students. Rather, I think the bulk of their political influence comes in the form of their ungodly massive investment in BCE, which perverts their interests and essentially makes their interests the same as the incumbent ruling class. All our power somehow seems to get turned against us.

Edit: Excuse me, I misremembered. It’s the pension plan that invests in BCE. Not sure if my point stands.

Last time I checked the OTPP wasn’t a major BCE shareholder. This seems to agree

But that doesn’t invalidate the general pattern. I think the ownership of a large corporation by a labor union or its pension plan is an improvement over traditional ownership. Reason being that the negative externalities produced by such a corporation are felt much more by the union’s members who have much lower incomes than some fat cats. As a result these members have on one hand the incentive to extract value from this corporation, but on the other the incentive to not overextract.

Another related thought I had some time ago is that if union density is very high and union members manage to extract the lion’s share of the company profits, then they’ll be able to accumulate much bigger savings. In such a reality the economic equation flips from having a financial system extract the value of labor for your pension to workers getting that value right in their paycheque, every two weeks. Of course there are other issues like some workers perhaps still not making enough for a decent pension due to the generally lower pay in some sectors. That’s why I think if union density goes high enough, we’d likely move to a much stronger national pension system.